Infectious Transmissions: Rina Banerjee in Two Dimensions

Loading...

Rina Banerjee’s sculpture–installations interrupt the gallery space, as she uses myriad media to create effusive, organic, overwhelming constructions that engage our senses. We are drawn to these detailed compilations of forms, and we are alert: they ask us to come close but they also seem to reach out towards us with a hint of threat. They are infectious, in all senses of the word. This infectiousness extends to Banerjee’s paintings, inviting and threatening and expanding well beyond their frames.1

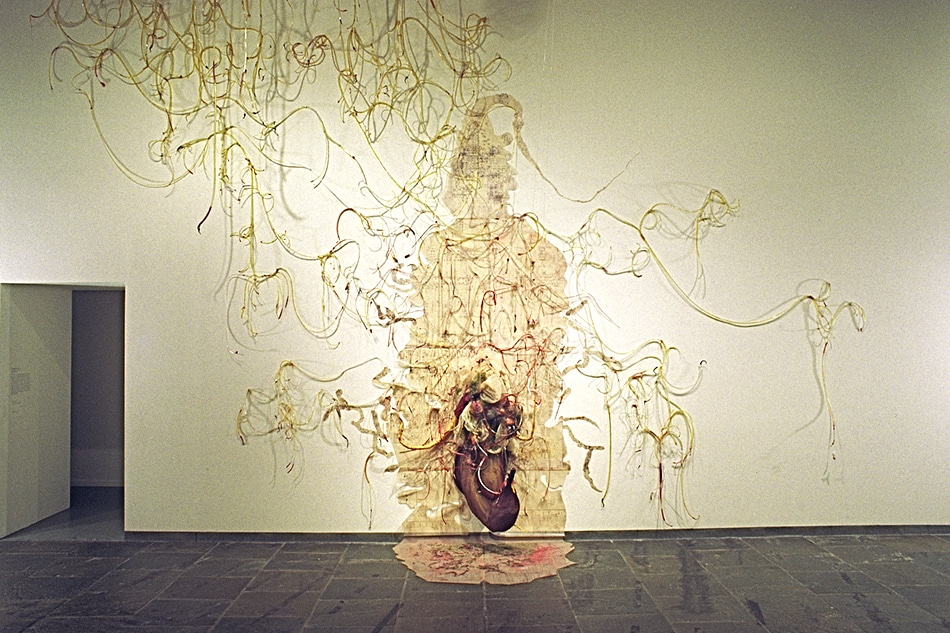

Room-sized installations have centered Banerjee’s practice from the beginning, but there was always the wall, and the two-dimensional was always gesturing to the three. In Infectious Migrations (2000), she assembled a wall-based sculpture that emerges from a blueprint on mylar—a plan of the air ducts and electrical wiring of a building at Columbia’s School of Public Health that Banerjee found.2 The plan shows, in two-dimensions, the pathways designed to move powerful forces into, through, and out of the building, enabling it to breathe, to energize itself, to support the work and life that it houses. That it is a health-related structure adds an appropriate twist to Banerjee’s use of it in 2000, as she built from it a critical engagement with the AIDS pandemic, as it continued to destroy lives across the world and particularly in Africa.

The building plan reappears in her later work—she copied it so that she could re-use it—as in Her black growth produced such a sprinkle of ultimate fears that a shadow of silver emerged from it to watch herself watching and followed all worldly movements (2006). Against the backdrop of the plan, which is oriented upside-down, two human-like figures float in a suspension of red, grey, and pink dots and blobs. The title suggests that this sprinkle might be seen as blood, bodily fluid, and a “black growth”—evoking black mold, a cancerous tumor, and also simply black body hair, aligning the foreign and intrusive with the natural, pointing to the way racism makes alien certain bodies, seeing them as intrusive or wrong.

The two bodies in the work are human but with a twist: the lower, green figure has four arms and perhaps three legs. Her fingers extrude long thin black fronds for nails, her shoulders sprout thin wings, her hair winds to the sky, sprouting grey leaves at its base and orange flowers at its crest. Sometimes her hair twists behind the pipes of the diagram, making visible their interpenetration. Her companion, whose gender is even less certain, has two profiles and seven eyes across their head, but their whole body is covered with eyes. Their feet sprout green fronds and their arms and tail seem to melt into a watercolor haze. Both figures expel lines of veiny blood and green vegetal growth from their mouths. The electric, mechanical, air-duct flows of the diagram are echoed by the bodies and their effluvia that float above and within in watery acknowledgement of the penetration of the alien into the organized heart of architectural engineering, of infrastructural building against the chaos and the intrusion of the other or the alien.

These meditations on the relation of bodies to space, and of flows of air and electricity to flows of blood, snot, semen, viscera, vaginal secretion, continue through the last two decades of Banerjee’s work. Bodies often float, whether fully immersed in liquid, as in Severed suddenly from land she swam, ran far for freedom (2015), or subtly unmoored from gravity, as in The durability of her beauty, polished fingers, her private and delicate proportions made all the city to know that she was a wonder… that only nature was able to ponder (2011). And their surfaces shift into transparency so that we can sometimes see through skin into inner workings offered not as anatomical plans but through daubs of paint, collaged pictures of teeth, or intrusive passages of dark, watery pigment.

Banerjee paints and draws on paper, but uses multiple media to effect this watery sensibility, using ink and acrylic alongside cut-outs of patterned paper and gold leaf. She experiments with frameless works, suspended away from the wall (Severed, for example), and also with paintings that appear mural-like, spreading outward in a flow of cut-out teardrop shaped forms to extend the work onto the gallery wall. Here, the gesture of Infectious Migrations, spreading outward and downward from the wall into three-dimensions finds its echo. In A myriad of voices (2019), these cutouts emerge from the painted sheets of paper, themselves attached to the wall with round-headed pushpins. The watercolor paper’s ragged edges don’t quite line up, and so while from a distance it feels like a site-specific painting done directly on the wall, on closer looking, one finds a painting on paper that has escaped to overrun the adjacent corner and wall. The full title underscores the import of this movement outward: A myriad of voices from beaten ground and buried folks, headless cries break even and odd broken sky to make sea to float like crackers baked by empires storm to make us hovel beneath, in whispers this blemish is wound, countable, not incorrect or surmountable so, so so — so what to do but come with feathered citizens and blow hard away this faceless fascism. Banerjee’s titles offer a parallel aural and textual gloss on the dynamism of her works. Here, the extended paper droplets make material and visual the strength of breath in the title. Or perhaps the central figure, whose armless fingers excrete droplets and drip lines of red, is drawing souls or life force up from the “beaten ground.” We can trace a transmission both into and out from this central figure: drops on her head flow into ribbons of red from between her legs; her mouth secretes brown patterned lozenges that pass by a human-headed bird who has her own word balloon. A trunk of colored lines curves upward from the level of her nose. She gathers the flow inward, then directs it out again. Transmission, flow, infection: fluids, sounds, breath, voice.

In 2000, Banerjee deployed a found architectural diagram of movement and power to ask us to contemplate the infection still raging across the world. Flows nourish but they also inundate, and they also slow to a trickle. The plan of air and electricity allowed Banerjee to unpack bodily relations, questions of transmission that echoed both disease vectors and histories of migration, “aliens” and othered bodies floating atop the ordered geometry of diagrams. Banerjee continues to explore the flows impeded and restricted by history, waiting to be severed suddenly and to swim, seeking out new modes of listening, feeling, catching buried voices. She offers us critical meditations on global pandemic, human migration, and the fragility and porosity of the body, inviting us to recognize our own infection, our own imbrication in these violent and visceral histories of transmission.

1. For an exceptional (in all senses) essay focused on her “drawings,” see Lauren Shell Dickens, “A Fluid She: The Drawings of Rina Banerjee,” in Jodi Throckmorton, ed. Rina Banerjee: Make Me a Summary of the World (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, San José: San José Museum of Art, 2018), 51–71.

2. Exhibition catalog: Maxwell I. Anderson, et al. Whitney Biennial: 2000 (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2000); review and reproduction of Banerjee’s contribution to the exhibition: Carol Vogel, “Choosing a Palette of Biennial Artists: Surprises in the Whitney’s Selections,” New York Times (8 December 1999), E1, E5.